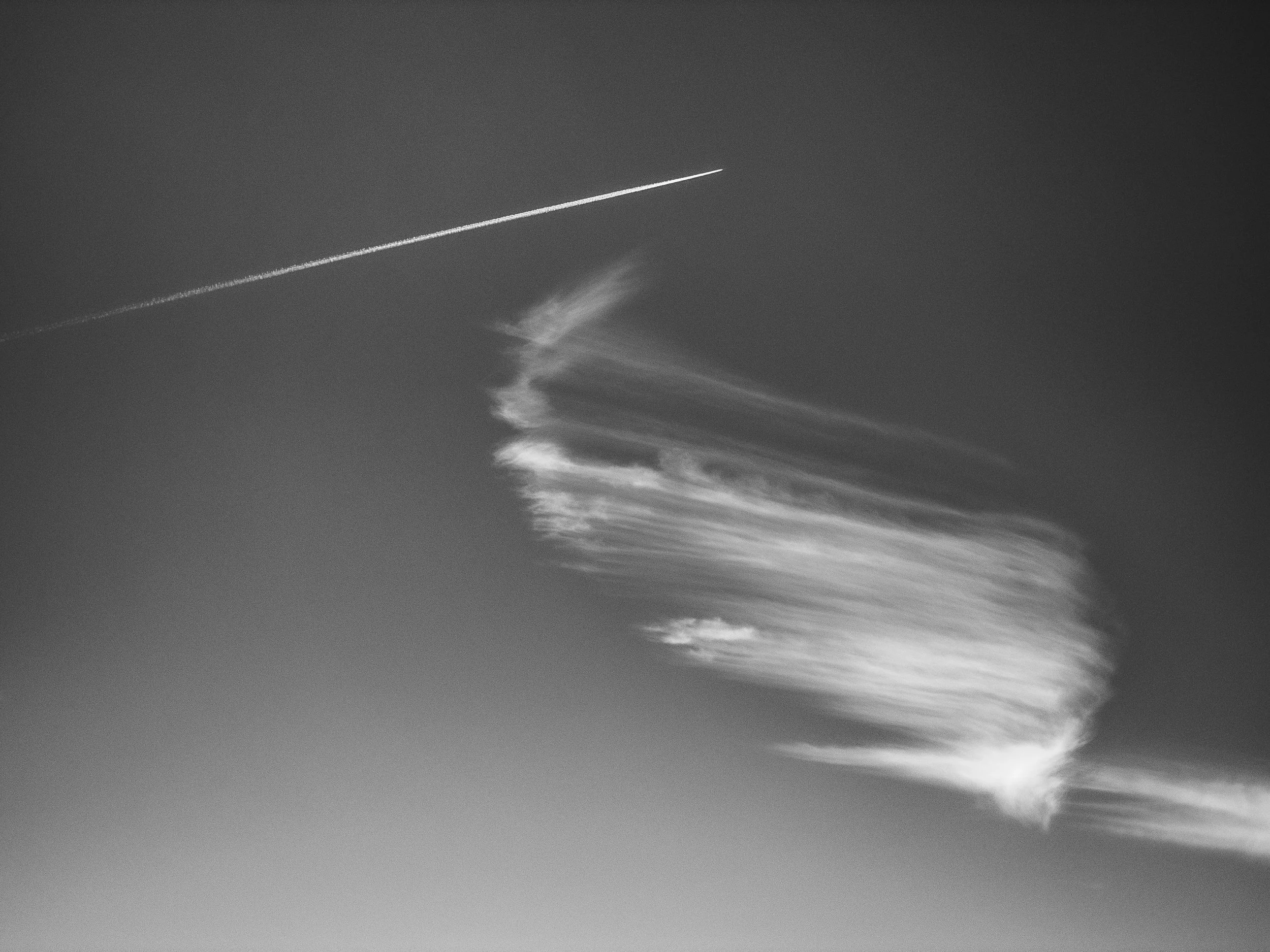

Contrails in a Cloudless Sky

“Look up,” she says, “and tell me what you see.”

So, dutiful, I do.

A calligraphy of mazy cloud, a pentimento of tumbled mare’s-tails, streaks diffusing like ink on wet paper, curls and windspun spirals, skewed vapor trails creeping horizonward, a razor-slash just born and still arcing a crowded sky. At its head the pinpoint, inching, of its genesis.

I try to describe it but she goes on, caring only that I have seen. “None are real,” she says. “Contrails not clouds. Artefacts of modernity. Evanescent and profound. Such intangible destruction.”

But seas away, destruction is tangible indeed. Will these contrails drift even there? Or they’ll be overcome by the infernos of revenge: billowings of ruin; plumes laden with concrete dust and DNA and the dreams and despairs of the fallen, all rising in furious contamination of borderless skies.

Our spewed particulates—fugitive contrails and pyres of the dispossessed—contest the warming of our other pollutants. We dim the sun even as we heat the world.

“Try to see,” she says, “from up there.”

Looking down, she means, from the contrails’ rarified altitudes onto the tragicomedy that is us.

“We had already begun trying to destroy ourselves,” she says, “when the skies were still pristine.”

Of course we did: our oldest most treasured stories are anthems of carnage. We build our faiths on plinths of violence. Our deities so decree and we, the faithful, hasten to comply. Lay waste, one god says, bearing the ark of the covenant before you. So the holy land disseminated its ancestral misanthropy across the lands and waters of creation to all the named and unnamed battlefields of human history: Troy and Gettysburg, Sand Creek and Khe Sanh, Hiroshima and Waterloo, Meuse-Argonne, Jericho, Mosul, Normandy, Okinawa.

And now Ukraine. And now Gaza.

How clearly can you see through the contrails of preconception? The directionless light through the scrim of hazed and virulent obsession flattens all the participants—actors, casualties, reluctant witnesses, zealots and infidels—into silhouetted caricatures devoid of nuance. Heroes and villains, a polarity of thems and usses.

“From your new elevation,” she says, “tell me: can you distinguish the victims? Can you identify the perpetrators?”

I am queasy with height. The ashes of the dead rise toward us, rise, to mingle with the miasma of the contrails’ leisurely demise. Is this ascension? I wonder. The lifting of the faithful to rejoin their respective callous gods?

“The victims,” I say, “are the children. And the perpetrators are the ones who prey on them.”

She smiles a sad smile. “But we are all children, aren’t we? Or were.”

At the question I am a child, still or again; a neophyte, staggering vulnerable and exposed across the killing fields.

“Who then?” I ask.

“All,” she says. “All victims. All culpable.”

“But …” I begin.

But. Old men orchestrate havoc and young men implement it, all for hollow causes to mask the underlying greed, rage, timeless feud. Like the perturbations of planetary bodies, their conflicts warp and drag the animus and bigotry of uninvolved observers across the continents, spreading with the gauzy obfuscation of the ubiquitous contrails.

“No,” I say. “I refuse to accept that. There are right and wrong … somewhere. Isn’t there an absolute? Somewhere?”

“Written in some book, you mean?” she says. “Is it sacred or profane, do you suppose?”

Because what possible god, I wonder, would countenance this, or even ordain it?

Some claim the land because a book deeded it to them somewhere in antiquity. Some claim the land because they’ve lived on it for millennia. Both claim the sponsorship of their respective gods, who might or might not be the selfsame deity.

At any given slice of time the contrails present a pattern—inscrutable, perhaps, but fixed. In the stasis of the single moment, though, the fluxion of history, of causality, of context is lost. The cryptography of the contrails contains but conceals Icarus’s ambition, Leonardo’s vision, the Wright brothers’ innovation, Neil Armstrong’s apotheosis. In the same slice of time the earthbound conflict exhibits a pattern too, subject to interpretation but equally bereft of deeper meaning. The battle for Gaza, another encrypted bequest, is a medieval melee where the apocryphal Egyptian escape, the shades of David and Goliath, the tide-lap of the Crusades, the pogroms of Europe, the seared memories of Auschwitz and the nakba, wrestle for relevance in a modern world enslaved to a brutish past.

I have no answer for her. She says, “What happens, do you suppose, when the oppressed becomes the oppressor?”

“It’s the eye for an eye syndrome, isn’t it?” I say.

“Ah,” she says, “the blinded world.”

But then must everyone in the end become their own myopic enemy? Is such a sorry eventuality foreordained by that cynical deity that injects itself into every scurrilous conflict?

Still looking down—through the shifting palette of the contrails, past the broken pillars of toxic smoke—I wonder if there are any answers, ever, after all. Or are we forever fated to sacrifice our children on the altars of our beliefs?

“Do you begin to see?” she says. “I’ve given you a proper vantage.”

Suddenly I turn to her, wondering for the first time where she came from; where I did. “Who are you?” I ask, or plead.

She smiles as if pleased. “I am the mother,” she says. “I am the lover. I am the antithesis of everything that’s going on … down there.”

Down there sounds like a curse. An epithet.

But down there is where we live. All of us, mired in the amber of our own bloody natures. I ask her, “But can’t you do something?”

“Of course not,” she says, “I’m only an allegory, a point of view. But you can.”

“Me? I’m just—” I begin, but falter.

“Just one person?” she prompts.

Dumbly, I nod.

“Everyone is just one person,” she says. “All eight billion of you.”

“Then how does it end?” I ask.

She hesitates; perhaps it is a secret not to be revealed. She sighs. “When enough have been blinded,” she says. “When enough can see. When the balance tips. When the sky is swept clean again, and the past can be forgiven.”

Then I’m back on the bloodstained ground, alone, watching the nursery of three world religions burn. On every side of the conflagration, everyone is so bloody right. Everyone is so bloody wrong. And I’m just one person, circumscribed by my own impotence.

One among eight billion.

And most of us, I finally realize, only want a place to stand, and some modest tomorrow to maybe dawn.

Lawrence Blair Goral

Bayfield, Colorado

29 November 2023